Travelling Far and Going Home

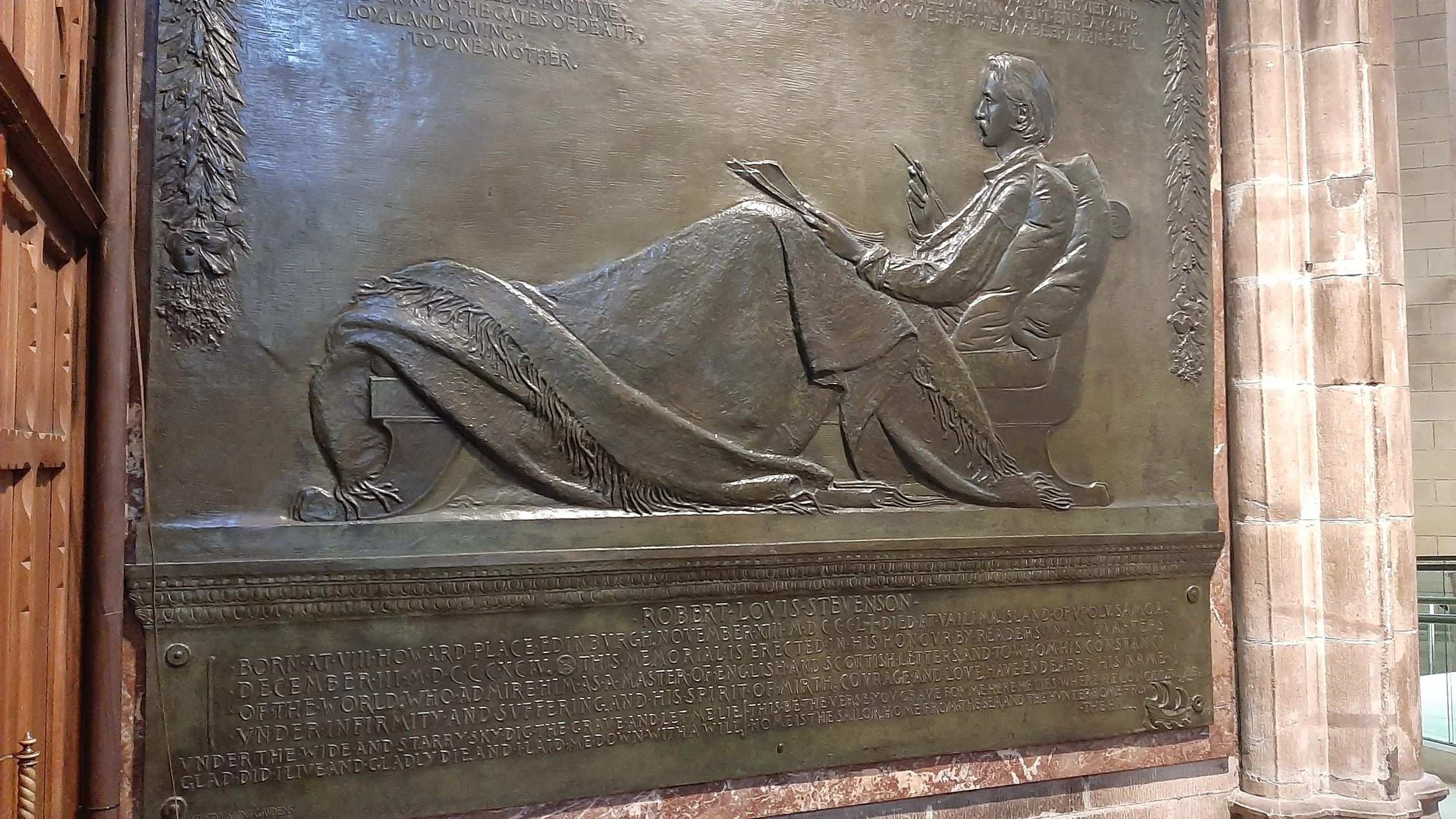

Picture: Robert Louis Stevenson reclining and writing. Bronze plaque in St Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, larger than life.

At The Writers’ Museum in Edinburgh, there is a quote from Robert Louis Stevenson: “We all belong to many countries…. For my part, I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move; to feel the needs and the hitches of our life more nearly; to come down off this feather-bed of civilisation, and find the globe granite underfoot and strewn with cutting flints.” (from one of his early novels, Travels with a Donkey)

In reading that, I thought that he was praising the life of the vagabond, of one who had no direction in travel, but who followed what the day brought. I think the world has changed. In our day, even travel is marked by “the feather-bed of civilisation”, and every nook and cranny has been marked out by an AirBnB entrepreneur.

Nevertheless, it is still true that “the great affair is to move”. When I go to an unfamiliar city, I like to walk, not necessarily to walk somewhere in particular, but just to get my feet on the ground, to get the feel of the place. Even at home, people like to walk; perhaps it’s a daily routine for them.

When Stevenson says, “we all belong to many countries”, I see it from the perspective of family history. I may be Australian, having been born here and lived here all my life, and being a fourth-generation Australian-born on both my father’s and mother’s sides.

However, my blood is English, Cornish, Scottish, and Irish. I still belong to many countries. It is not pretension that makes me say that going to Britain or Ireland is like going back home, and it takes nothing away from where I see my roots. I have been a child of Australia for a long time. When the kookaburra laughs, it marks my neighbourhood, or, it puts its mark on me.

Then, when I have travelled a while, I like to come home. Stevenson also liked to have a place to return to, to sit and write. In 1887 he published a collection of poems, Underwoods, and in it he suggested the inscription for his grave:

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

Clearly, we need both near and far: home and distance, stability and adventure. At The Writers’ Centre, I bought a copy of Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses. It has a poem called “The Lamplighter”. His name is Leery. The child says,

My tea is nearly ready and the sun has left the sky;

It’s time to take the window and see Leery going by;

For every night at teatime and before you take your seat,

With lantern and with ladder he comes posting up the street.”

Leery offers to the people of the town the regular perfection of a gentle light at night. In my family tree I have one ancestor who was a lamplighter, so I imagine him as one of the essential elements of a stable community.

While I was away I found, in a bookshop (also in Edinburgh), a book on the philosophy of the home. It seemed obvious to me when I saw it that someone had to take up this subject, and I wondered why it had not been done before (the initial publication date was recent: 2021). As the writer, Emanuele Coccia, says in the Introduction, “sooner or later we must return home”. It is not a matter of architecture or ownership, because it may be a fold-up tent that moves with us, but it is a place where we feel safe, and whose intimacy makes happiness possible. Our jostling and negotiations with the outside world need this counterpoint.

I imagine that most people, presented with this definition, would find it hard to argue with it. Yet, as Stevenson asserts, we also need to travel and discover the unfamiliar. In the book that I have now published, The Traveller, Lost, I got lost more often than I thought possible, or appropriate, but I did discover many unfamiliar things, many of which were delightful.

Coccia concludes his book by saying that we must see the entire planet as our home. This is true, in the sense that we must care for the planet as much as we care for our intimate surroundings. But, as my getting lost shows, we will always find the world to be bigger than us, even armed with technology that is supposed to ensure that we never get lost.