Where did I come from? A sensitive subject

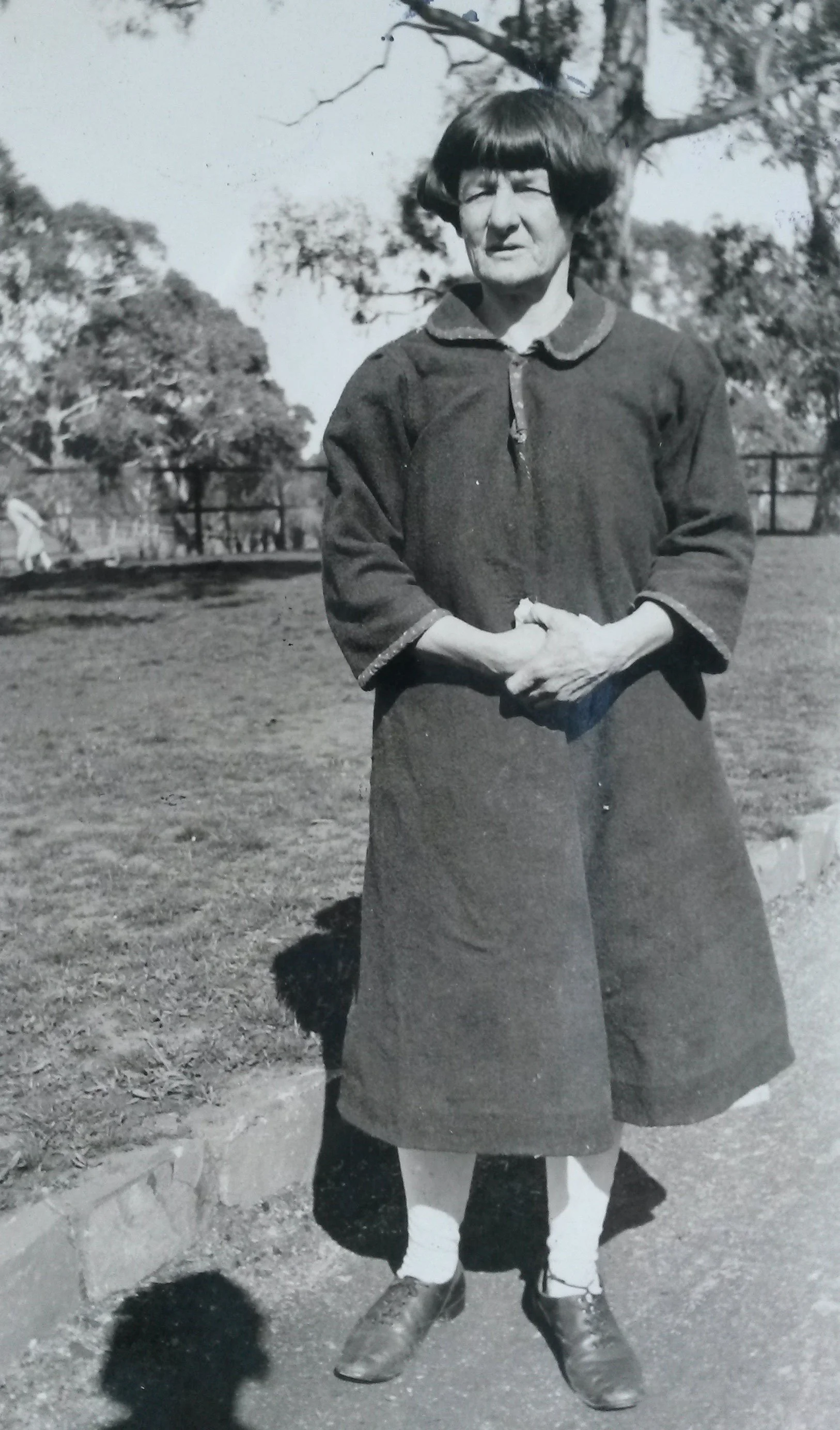

Elizabeth Martin, about 1949, at Bloomfield Hospital, Orange. Elizabeth was my father’s mother.

Once, I didn’t come from anywhere. We had parents, that’s all, and they said they had parents, but that was only once upon a time. I had the idea that once you grew up, your parents disappeared from your life. All the time I was growing up, my mother said she thought she would die before she turned fifty. Just before I turned seventeen, my father died suddenly of a heart attack; he was fifty-three.

Nor did I come from a place that had a past. Until I was four, we lived with my father’s older brother. Then we moved to a new suburb of Sydney, Chullora, into a ‘temporary dwelling’, a fibro shack. The surroundings were scrappy bush: not a forest or a meadow, the seaside or the riverside; not the hills. In time, we built a new, modest, fibro house. Around us, other families built their own modest houses. There was no past.

But I did wonder. However, life is busy. In adulthood, there was work, my own family, getting my own house, surviving.

When my mother turned ninety, she had a lunch with guests, and I looked around at the folks, which included a few of my cousins. I knew nothing, and suddenly I felt that I should know. That’s when my family history research began.

There were few people left to ask. I had learned some stories from mum. As I progressed, I found that some of those stories were not quite right. That was interesting, because I wondered why that was. My progress was based on certificates, once I learned how to acquire sufficient details to order the right ones. It was a step-by-step process. Mum showed me the certificate from her marriage to dad, and his death certificate.

My mother’s parents were Thomas Richard Archer and Margaret Florence Mackie. That information came easily enough. And yes, Thomas died in 1936 at the age of fifty; my mother had been twelve. Margaret died in 1941 at fifty-three (mum was seventeen). Perhaps this was why my mother had the irrational belief that she would die before she turned fifty.

Much harder to find were my father’s parents. All I had from dad’s death certificate were the names: William Thomas Martin, blacksmith, and Elizabeth Eggleston. Blacksmith? Dad had been a painter; no connection. He had been a quiet man, and had never said anything about his past. But now I had this obstinate idea that I did have a past, and William and Elizabeth were part of it, whoever they were.

My mother’s side of the family had a story. There was a hotel, the Duke of Edinburgh at Pyrmont, and an ancestor had built it. Then there were lots of children, who also had children, and my mother was one of the descendants. I didn’t know the details, but it formed a picture. For dad’s family I had nothing. Or, perhaps what I had was silence; so, I was determined.

I never pressed my mother. That would have been wrong, as well as unproductive. I could tell there were sensitivities around dad’s past. When I visited her at Ballina, I talked generally about my inquiries into family history, and I told her about people I had found that were interesting, if I thought it would not be threatening. And she used to write me short letters occasionally.

One time she said, “Keep looking. You never know what you will find.” Amidst the guardedness that I felt from her about certain areas of the past, this was encouragement. I wondered if she was encouraging me despite herself. Then, on one of my visits she told me, “I think your father’s mother was admitted to Callan Park around 1920.” I had gathered enough already to suspect that something like this had happened (although I didn’t know what or why), and this was the clue I needed. I think she was letting me know before she died. (She died a couple of years later.)

She talked about it then: that after several children, the mother had another baby and she was not in her right mind to look after the baby; she was raving, she tried to poison herself. So she went into an institution, and the family was split up, and dad (who was seven) was raised by an uncle and aunt. She also said that when she and dad were getting married, they asked a doctor if the problem could be hereditary. So, I gathered there had been bewilderment and concern. The doctor said no.

My quest now was straightforward. I wrote to the Department of Health, enclosing proof of my connection to Elizabeth Martin, and requested access to her file. When I went to the counter at State Archives to retrieve the file, the lady opened it and showed me a photo. She said, “It is rare to find a photo in these files.” It was Elizabeth Martin, probably in the late 1940s. Finally, a person. Not a happy one, but a real person, my grandmother.

The file was unhappy reading. She had not got out of the institution. She was transferred to a new hospital at Orange (Bloomfield) in 1930 and had died there in 1957. That was a shock: she had not died until I was seven. On my parents’ marriage certificate (1947) she is described as ‘deceased’. I understand why: conventions are implacable, but it is still painful knowledge.

In the wake of this discovery, I was able to find the death of William Thomas Martin. He had died at Annandale (Sydney) in 1955: another grandparent who had been alive when I was born. Much later I found that there was a rich history of miners in the Martin family, going back to Cornwall, and the ‘blacksmith’ label was, from our time’s perspective, a misnomer. He was more of an engineer.

Does it matter that I have a past? Yes, it does. Not to have a past is to be marooned. We all come from the earth, however rough or bitter. We all have a long past. We dwell in its surprises.